Our friends from Corsair published an informative blog which I’ve decided to repost here in full to show you how memory speed past DDR3-1600 benefits your daily PC usage on Haswell (Z87) platform. A lot of people are not well informed about this and it’s time to show some testing and examples to inform you why having high speed RAM and a motherboard that is well tuned to run such speeds and timings is important for your daily PCs and why DD3-1600 is just not good enough any more!

It’s a very nice read and for those that are unaware you are literally a few clicks away from getting high speed on your rigs with Gigabyte motherboards provided your memory is capable. In my event hopping outings I occasionally hear confessions from people at LANs saying they purchased high speed ram and still run it at bios defaults. If you’re one of those people, I hope you watch this video I’ve prepared quickly and read the article to understand why it’s important to use that extra speed and timings. Here is a video first showing how to enable XMP profile on Gigabyte boards:

Haswell Real World Performance: DDR3-1600 RAM Speed Is Not Enough

The prevailing wisdom in the enthusiast community has been, for generations, that DDR3-1600 is the sweet spot and that faster memory offers at best extremely limited performance improvement and that at worst, it’s snake oil. There’s an element of truth to that; AMD’s Bulldozer architecture and its derivatives see arguably minimal benefit from faster memory, and Ivy Bridge and its predecessors actually were just fine at DDR3-1600. So the idea that the paradigm might have shifted is tough to swallow because it goes against wisdom that’s been ingrained for years, a veritable lifetime in our industry.

Except that it has. DDR3-1600 is quite simply no longer enough for modern chips outside of Ivy Bridge-E and Vishera. That Kaveri benefits from faster memory (at least on the GPU side) is a foregone conclusion that was confirmed by our testing. AnandTech already exhaustively detailed performance scaling with different memory speeds on Haswell, and I’ve studied the effect of memory speed on Battlefield 4’s performance. Between our work and AnandTech’s extremely thorough research, you’d think there would finally be a pervasive understanding of the benefit of faster memory on Haswell, but that hasn’t been the case.

I originally went into this testing specifically trying to determine whether or not overclocking would increase the strain enough on Haswell’s memory controller to justify higher speed memory. In testing, I discovered fairly conclusively that DDR3-1600 essentially leaves performance on the table even at stock clocks.

For testing I ran Intel’s Core i7-4770K at stock speeds and overclocked to 4.5GHz. A 32GB (4x8GB) kit of our Dominator Platinum DDR3-2400 was used to scale from DDR3-1600 CAS 9 to DDR3-2400 CAS 10. Test system specs are as follows:

Intel Core i7-4770K CPU

Stock Speed (3.5GHz nominal, turbo to 3.7GHz on four cores or 3.9GHz on one core)

Overclocked (4.5GHz, 45x100 BClk, 4GHz Northbridge

Gigabyte G1.Sniper 5 Motherboard

4x8GB Corsair Dominator Platinum DDR3-2400

DDR3-1600 (9-9-9-24 CR2)

DDR3-1866 (9-9-9-24 CR2)

DDR3-2133 (10-11-11-31 CR2)

DDR3-2400 (10-12-12-32 CR2)

NVIDIA GeForce GTX 780 Overclocked (980MHz nominal, boost to 1150MHz, 7GHz GDDR5)

240GB & 480GB Neutron GTX SSDs (for Adobe testing)

I very deliberately chose a mixture of synthetic and real world benchmarks. Cherry picked synthetics can admittedly overstate the importance of higher speed memory; I wanted tangible, demonstrable, practical benefits.

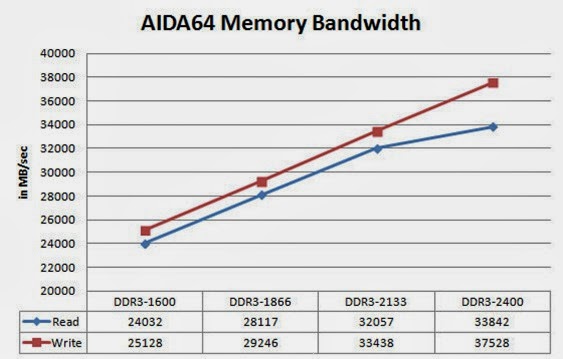

Overclocking the CPU itself had virtually no effect on memory bandwidth, producing results essentially within the margin of error. We’re just going to measure the raw amount of bandwidth made available to the i7 as memory clocks increase.

There’s a very steady increase in bandwidth going from step to step, but read speed tapers off moving from DDR3-2133 to DDR3-2400. This isn’t surprising; Kaveri also started to get shaky around DDR3-2400. Discovering Haswell’s memory controller’s “breaking point” may be worth looking into in the future. Nonetheless, we’re seeing roughly 18% improvements in raw memory bandwidth at each step until DDR3-2400.

Now we’ll see if that translates at all in the two synthetic benchmarks I’ve included. First up is the x264 HD 5.0 benchmark, which absolutely hammers the CPU.

This benchmark is almost entirely CPU limited, but there are trends to point out: overclocking increases the effect memory bandwidth has on performance (proving the initial hypothesis), and the jump from DDR3-1600 to DDR3-1866 is the most significant. The second pass sits almost entirely on the CPU and absolutely hammers it, but the first pass is able to eke out small gains.

The next synthetic is the built-in benchmark in 7-Zip. WinRAR has long been a stronghold of fast memory, but I haven’t used it in ages; 7-Zip is free, fast, and it works.

7-Zip shows modest but steady increases in performance as memory speed goes up, with an unusual jump at DDR3-2400 at stock. These aren’t the kinds of massive gains you might see in WinRAR, but they’re definitely present.

Where things really get interesting are with my two big practical benchmarks: Adobe Media Encoder CC and StarCraft II: Heart of the Swarm.

Both of these benchmarks were run with CUDA acceleration enabled in Mercury Playback Engine, and both of them see substantial improvements in running time. The AVCHD encode is able to shave off about 10 seconds, while you can save a full minute with the HDV encode. In fact, on the HDV encode, running the stock CPU with DDR3-2133 or DDR3-2400 instead of DDR3-1600 actually gets you pretty close to the 4.5GHz overclock with DDR3-1600.

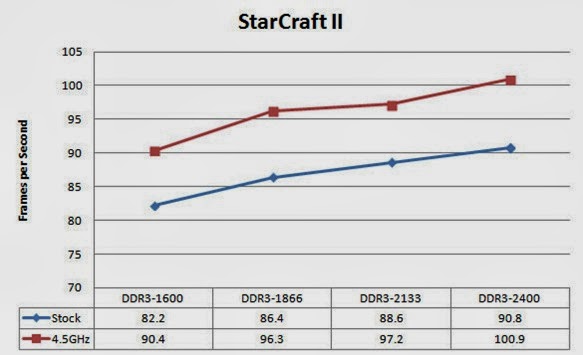

The Hail Mary in the group is StarCraft II: Heart of the Swarm. Testing was done at 1080p with all of the settings maxed out, so it at least looks the same way it might on your home system. This is also one of the few games that could theoretically benefit from a framerate higher than 60fps, and any kind of demonstrable performance benefit on the CPU/memory side is valuable.

If you run the i7 at stock with DDR3-2400, it’s basically as fast as a 4.5GHz i7 with DDR3-1600. Bump the 4.5GHz chip’s memory to DDR3-1866 and it starts to soar. Getting roughly 10fps out of something as simple as faster memory is staggering.

When we take a look at the performance results holistically, we see our real world benchmarks are able to eke out a minimum of 5% improved performance by going up to DDR3-2133; even going up to DDR3-1866 still nets a solid jump. DDR3-2400 still has plenty to offer in some cases. Add overclocking to the mix and the performance gaps widen even more.

As far as I’m concerned, the conclusion is simple: DDR3-1600 isn’t enough for Haswell, and it leaves performance on the table. This testing was done with DDR3-1600 CAS 9, when DDR3-1600 CAS 11 is actually exceedingly common and thus even slower. If we’re willing to overclock every component in our system to extract as much as five or ten percent more performance, it seems absurd at this point to cheap out on memory. You can get 16GB of DDR3-1866 CAS 9 for nearly the same price as 16GB of DDR3-1600 CAS 9 on our web store, and DDR3-2133 CAS 10 or CAS 11 isn’t much more than that.

With Haswell I continue to be convinced that DDR3-1866 is the new entry level, and that DDR3-2133 is really the sweet spot. Performance improvements from DDR3-2133 to expensive DDR3-2400 are less consistent, and Haswell’s IMC itself starts to get a little shaky there. I may do more testing in the future to determine where the IMC’s limit is; my experience was that under some circumstances, there’s a slight performance regression from DDR3-2400 when you get to DDR3-3000 (which is an absolutely ridiculous speed). In the meantime, the conclusion remains clear: for modern and especially high performance Haswell and Kaveri systems, DDR3-1600 isn’t enough.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.